In the current administration, senior officials come and go with such revolving-door frequency, it’s hard to remember a time when chief cabinet appointments carried a sense of hallowed gravitas. The concept of the statesperson, representing democratic ideals and rolling up their sleeves in diplomacy and policy-making around the world under the banner of collective betterment, is certainly in danger of becoming obsolete. And yet, when Madeleine Albright was appointed secretary of state under President Bill Clinton in 1997, she radically broke a number of old concepts about what it meant to be a “statesman” as well—not least among them, the fact that Albright was the first woman to assume the post in the history of the United States. Albright’s intelligence, perseverance, and humanity on matters of foreign policy during her four-year tenure are already the celebrated stuff of awards, medals, and honorary degrees (as well as a bestselling memoir on her time working in the Clinton administration on such volatile regions as the Balkans and the Middle East). But Albright didn’t stop being a public servant and outspoken citizen when she left the White House in 2001. For the past two decades, she’s been fighting the good fight, giving lectures, writing books, championing the salvational powers of democracy, supporting and advocating women’s rights all over the map, and, at every turn, reminding us that the art of diplomacy is about listening as well as talking. Albright has had a very busy 21st century, during which she seems to have done everything but slow down.

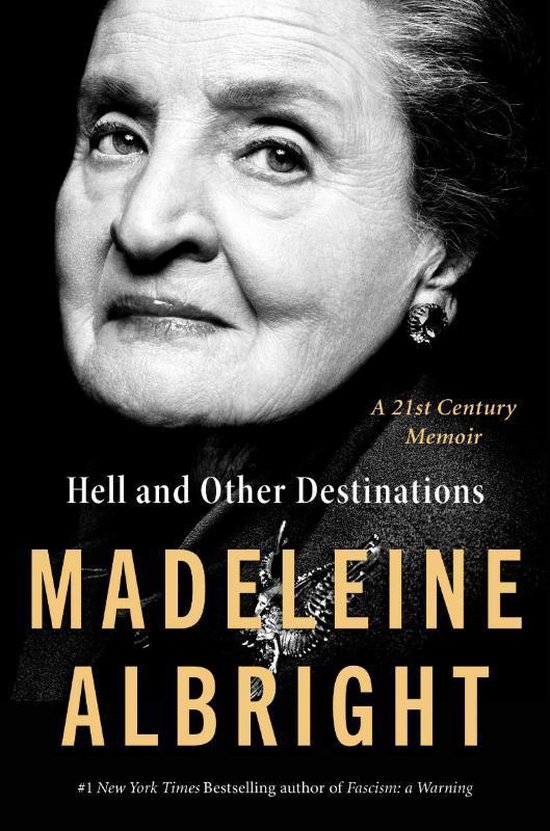

Her new memoir, Hell and Other Destinations, out this month from HarperCollins, leaps through all of her public and private activities in the past 20 years. The whole time, Albright is constantly asking, “What’s next?” When she wasn’t stumping for Hillary Clinton during her presidential election bid or penning a book on the subject of fascism, Albright also found the time to cameo on more than one television show. In the last season of Parks and Recreation, Albright eats waffles in a D.C. diner with the exasperated do-gooder protagonist Leslie Knope (Knope finally concedes to give back Albright’s eagle brooch). As it turns out, the actor Amy Poehler is just as big of a fan of the former Madam Secretary as her onscreen character. She asked the 82-year-old political titan about fighting for women, anxiety dreams, and the upticks of being short.

Hell and Other Destinations is an illuminating volume that presents a selection of Read's most elegant and memorable writings on subjects ranging from Christians and Jews, liberation theology, and The Da Vinci Code to sexual desire, saints and Pope Benedict XVI. Customers Who Bought This Item Also Bought The Poor Old Liberal Arts.

———

AMY POEHLER: I’ve been reading your new book, which is part essay, part memoir, part informational, observational genius. And the title alone is so great!

- Hell and Other Destinations: A 21st-Century Memoir Madeleine Albright, with Bill Woodward. Harper, $29.99 (400p) ISBN 978-0-06-280225-5. More By and About This Author. An Optimist Who.

- Apr 14, 2020 HELL AND OTHER DESTINATIONS A 21ST-CENTURY MEMOIR by Madeleine Albright ‧ RELEASE DATE: April 14, 2020 The former secretary of state reflects on the world that has emerged since she left office in 2001.

- May 01, 2020 Hell and Other Destinations Just out: Hell and Other Destinations by former Secretary of State Madeleine Albright.' For nearly twenty years, Albright has been in constant motion, navigating half a dozen professions, clashing with presidents and prime ministers, learning every day. Since leaving the State Department, she has.

Hell And Other Destinations Audiobook

MADELEINE ALBRIGHT: Yes, it raises eyebrows.

POEHLER: What made you title it Hell and Other Destinations?

ALBRIGHT: Well, there are really three reasons. First, all you have to do is look at the news. If we don’t wake up soon and start doing things differently, hell is precisely where we’re headed. The second reason has to do with a saying I have, which you might have heard: that there is a special place in hell for women who don’t help each other. The third reason is that the ideal title might have been Parks and Recreation, but that was taken. So add it up and there we are.

POEHLER: This is your seventh book. That’s a lot of books, Madeleine Albright!

ALBRIGHT: Call me Madeleine. We must be on a first-name basis here.

POEHLER: I know, but I love that Madeleine also sounds like “Madam,” and I like calling you that. What was the difference in writing this book from the previous ones?

ALBRIGHT: This is the third book dealing with how my life has been. There was Madam Secretary [2003] where I went through what I’ve done officially. Then there was Prague Winter [2012], which goes back into my family background and how I got to be who I am. This one came out of people asking me an awful lot about what I’m doing and how it all fits together. Because I can sound like a bit of a nutcase to people! I just got off an airplane and the flight attendant looked at me and said, “Can I be rude and ask how old you are?” I think people expect me to shut up at this point!

POEHLER: You know what? As a woman of middle age, ageism is a real thing that exists in our country. People are obsessed with youth culture and the new. What I love about you is how you want every stage of your life to be more exciting than the last. You write about that in the book, and it’s so inspiring to read about a woman in, as you would say, the “third act” of things, who is more curious and vibrant than ever. How do you fight ageism?

ALBRIGHT: I think there’s always the cliché: It’s just a number and not how you feel and what you do. In the case of my generation—or at least for me—it took a long time to get started. I was always ten years older than everybody right from the beginning because I got married very early. I had children when I was 24 and it took me forever to get my PhD. But one needs to look at what is interesting and what keeps one going. In case you can’t tell, I’m a total extrovert and energized by people. I feel better when I’m doing things! But it took me a long time to find my voice, and I’m not going to shut up now, so I might as well use the things I’ve learned and care about deeply while I’m kicking.

Hell And Other Destinations Review

POEHLER: You talk about how much you’ve learned from being around young people. What are you learning these days from the young?

ALBRIGHT: I teach at Georgetown, and I also go around to a lot of other schools. There’s an institute in my name now at Wellesley, and I was just up there with a bunch of young women who are working on all kinds of exciting projects. What I’ve learned is that they are much more into exploring opportunities and making a difference than a lot of us were when we were younger. I’m not making that up. I think they truly are motivated. They don’t want to just sit around and accept things. And they argue! I love it in my class when I’m challenged because then we can have a discussion. It may be because I teach international relations, but I have so many students who speak more than one language; many are foreign students or first-generation, and many have traveled. And they are not at all placid.

POEHLER: It must be interesting as a mentor to watch people fight in real-time and find their voice.

ALBRIGHT: I urge them to do that. But at the same time I want them to respect the ideas of others. I do believe in having civil discussions and thinking that you can learn from people that disagree with you.

POEHLER: We’re really lacking in civil discourse these days. And you’ve basically made a career of having to be in rooms with people that you don’t necessarily agree with. How do you, Madeleine, run a room, and what are ways in which people can feel heard? I think we’re desperate for that right now, for people with differ ing opinions to feel heard.

ALBRIGHT: I think you’re right. And I think a lot of those skills come from having lived in a lot of different places and trying to figure out the culture or history of X place. I just came back from London, and I was a few blocks from the neighborhood where we lived in World War II during the Blitz. Then I was at the Munich Security Conference and there were a lot of people there from the Balkans and I spent a lot of time on the issues there. Basically, my past life made me want to listen to other people. In order to be a good diplomat, you have to put yourself into other people’s shoes. That’s my MO. The part that’s hard is when you’ve got a room where some people are so bent on putting their view forward that they don’t give other people a chance. In that case, something I used to do as a diplomat is say, “I have come a long way and I must be frank, you have to listen to what X wants to say.” There’s no way to have a useful conversation if everyone just repeats the same things and doesn’t want to hear what other people are saying. We’ve got this saying: “See something, say something.” I add, “Do something.” One of my to-do’s was to be respectful of other people’s views and try to understand what they are saying.

POEHLER: That’s what I love about your writing. It deals with giant, macro thoughts and ideas, but it also comes down to these essential lessons to practice in everyday life about a sense of self and what we care about. What I’m trying to say, Madeleine, is that I feel like you and I have had the same life. Is that weird?

ALBRIGHT: It isn’t weird. Anyone can go around and beat their chest and say, “I’m right, I’m right, I’m the smartest person in the world.” But if you don’t hear what others are saying, you are missing the ability to analyze what is going on in friendships or small towns or the larger world. It’s a basic aspect in terms of figuring out how you relate to another human being. One of the things that I hope comes through in this book is that every individual counts and there is something that has created that person to be that way. It’s like being an investigator, trying to figure out where they come from. I find it challenging and you do too.

POEHLER: I think that having an openness and curiosity about people is one way out of a lot of messes. And we’re living in a time where our news and our president and our politics makes everybody feel like they’re more separate than ever. Do you think that we are, as a world, closer right now or farther apart?

ALBRIGHT: Well, both. There are positives and downsides to two mega-trends. One is globalization. That means we travel and see more, but it can also lead to a certain kind of facelessness. I do think we all want to know who we are. What’s bad is when my identity hates your identity and you decide, “I just want to be with my people.” The other one is technology, which is stunningly complicated. I think about the Kenyan woman farmer who no longer has to walk miles to pay her bill. She can do it over her phone, and she has time to spend with her family or get an education or start a business. That’s the upside. The downside is that everybody gets their information their own way. They don’t know where they got it and they don’t know whether it’s true or not, and so there are huge divisions based on the perception of facts. So, to answer your question, it’s both. It’s a very complicated time both domestically and internationally. When I’m trying to be very direct, I say, “The world is a mess.” That’s the diplomatic term there.

POEHLER: There’s such a void in leadership, so much contentious language, and so much fear-based governing. It’s hard not to fall into despair, and as we all know, despair can paralyze you. You’ve gone through so many different administrations. What keeps you motivated and engaged?

ALBRIGHT: I’m a doer. And I think my greatest talent is dot connection, which is one thing leading to another. My passion is a democracy writ large. I believe that we’re all the same, and people want to be able to make decisions about their own lives. And one of the things we know is that economic and political development go together. Democracy has to deliver, because people want to vote and eat. So there has to be a way of trying to figure out how those things go together and how to get the private sector more involved in figuring out solutions to some of the dreadful problems. I’m motivated by the fact that it doesn’t prove anything to sit around and moan and groan, that doing something is important. By the way, the more I know about what happened to my family, and how, by being a refugee twice, in many ways it’s an accident of history that I exist. So I figure I have a responsibility, and I do call myself a grateful American.

POEHLER: Madeleine, do you ever dream about being in other countries? Do you dream in different languages?

ALBRIGHT: I do sometimes. When I’m in a setting where I’ve just been speaking a language a lot, then I do dream in that language. I have fun dreams and some that are creepy or scary. One of the dreams I will never forget is when I had just been named secretary of state. I always had dreams of rushing for planes that were pulling away from the gate because I was late. And all of a sudden in my dream, the plane was waiting for me so I could get on. That seemed symbolic.

POEHLER: You have three daughters.

ALBRIGHT: Yes. And six grandchildren!

POEHLER: What was important to instill in your daughters when you were raising them? What did you want them to know or feel as young women growing up in this world?

ALBRIGHT: I have to admit the following thing. When they were growing up, a lot of other women made me feel guilty. That’s part of the “special place in hell” thing, because we’re very judgmental about each other. So I was nervous about whether I was a good mother or not. But what my daughters now say I instilled in them was the desire to work hard and do things that help other people. One is a judge, one is running an international program about education for young people, and one headed an organization to prevent the abuse of children. So they have done what I wanted them to do.

POEHLER: You must be so proud. That’s every mother’s dream, is to watch their children find what they’re passionate about and do it. How awesome.

ALBRIGHT: I do ask them occasionally whether I was a bad mother, and they obviously say no, but I do wonder. I do think every woman’s middle name is guilt.

POEHLER: One hundred percent. I’m always shocked when I’m in meetings or at work or working where people always ask me, “So where are your kids?” Or, “Is it hard for you to be away from them?” It’s still a question that’s asked all the time to women and not to their male counterparts. It’s really our job to reject hat and to support each other and to try to get that guilt out of our middle names.

ALBRIGHT: I am so often asked about life balance, and I give this example of the complication. I left my youngest daughter’s wedding reception early so that I could join Hillary Clinton to go to the Beijing World Conference on Women. A lot of my female students say, “How do you do it?” The bottom line is that everybody has to find their way. There’s no one answer to it. But I do think we’re hard on each other, I really do, and that’s where my statement about hell came from. Specifically, the kind of things that people said to me.

POEHLER: I think you’re right. We are hard on each other, and one of the ways that we can practice compassion is to be easier to each other and to ourselves. We’re human beings. I do want to ask, as a fellow short woman, what’s one of the best things about being short? I think it’s probably good for travel, right?

ALBRIGHT: Well, it is good. The truth is that the seats are more comfortable. I don’t have to worry about leg space. But I have to say, this hasn’t happened to you yet, but I keep getting shorter and shorter. I’m trying to figure out at what stage this all stops. But the hardest thing about being short is when you’re in a photo line and the person on the other side, male or female, is so much taller than you are, and you think, “Okay, how is this going to work?”

POEHLER: It just goes back to what we were talking about, that power comes in many forms. There’s sometimes an advantage to being underestimated, and as a smaller woman, physicality isn’t always the way in which you can command power and respect. It’s like when you’re being attacked by a bear, you’re supposed to make yourself bigger. But also, as a short person, you can curl up in a ball and hide, and maybe the bear will just bat you around and leave you alone.

ALBRIGHT: People have come up to me and said, “You’re so much shorter than I thought you were,” because I stand on a box to give a speech. But I do think the job made me seem taller.

POEHLER: Well, you are a giant in my eyes, Madeleine. It was truly such an unbelievable day when I got to meet you in D.C. when we shot that scene together [for Parks and Recreation]. One of the best things about playing my character, Leslie Knope, is that she’s so enthusiastic she gets to gush in real-time about people that she loves. So I got to do the same to you in our scene, but I felt the same behind the scenes too.

ALBRIGHT: I feel the same way about you. I do actually watch a lot of television and I look for the messages that are being sent. I think you give a very strong message about what it is like to be a gutsy woman. I think it’s a very important message, and I’m very glad to share that kind of capability and love of what one does with you. Did I ever think you and I would actually become really good friends? I think we’ve gotten there.

Video Albright Hell And Other Destinations

POEHLER: Me too. Next time we’re in the same city, I’d love to take you out to lunch and congratulate you on your wonderful book. And also to check out your new brooch. I want to see what kind of brooch you’re rocking these days.

ALBRIGHT: I have one that I bought at the National Czech and Slovak Museum, because they are very good at making crystal things. I’ll wear that for the book tour!

———

Hell And Other Destinations Audiobook

Makeup: Rachel Lane

Photography Assistant: Julian Hibbard